Zambia’s misplaced language invented by girls however nearly killed by colonialism

Girls’s Historical past Museum Zambia

Girls’s Historical past Museum ZambiaA wood hunters’ toolbox inscribed with an historic writing system from Zambia has been making waves on social media.

“We have grown up being instructed that Africans did not know methods to learn and write,” says Samba Yonga, one of many founders of the digital Girls’s Historical past Museum of Zambia.

“However we had our personal manner of writing and transmitting data that has been utterly side-lined and ignored,” she tells the BBC.

It was one of many artefacts that launched an internet marketing campaign to focus on girls’s roles in pre-colonial communities – and revive cultural heritages nearly erased by colonialism.

One other intriguing object is an intricately embellished leather-based cloak not seen in Zambia for greater than 100 years.

“The artefacts signify a historical past that issues – and a historical past that’s largely unknown,” says Yonga.

“Our relationship with our cultural heritage has been disrupted and obscured by the colonial expertise.

“It is also stunning simply how a lot the function of girls has been intentionally eliminated.”

Girls’s Historical past Museum Zambia

Girls’s Historical past Museum ZambiaHowever, says Yonga, “there is a resurgence, a necessity and a starvation to attach with our cultural heritage – and reclaim who we’re, whether or not by vogue, music or educational research”.

“We had our personal language of affection, of magnificence,” she says. “We had ways in which we took care of our well being and the environment. We had prosperity, union, respect, mind.”

A complete of fifty objects have been posted on social media – alongside details about their significance and goal that exhibits that girls had been usually on the coronary heart of a society’s perception techniques and understanding of the pure world.

The pictures of the objects are offered inside a body – enjoying on the concept a encompass can affect the way you take a look at and understand an image. In the identical manner that British colonialism distorted Zambian histories – by the systematic silencing and destruction of native knowledge and practices.

The Body mission is utilizing social media to push again in opposition to the still-common concept that African societies didn’t have their very own data techniques.

The objects had been largely collected throughout the colonial period and saved in storage in museums all around the world, together with Sweden – the place the journey for this present social media mission started in 2019.

Yonga was visiting the capital, Stockholm, and a pal recommended that she meet Michael Barrett, one of many curators of the Nationwide Museums of World Cultures in Sweden.

She did – and when he requested her what nation she was from, Yonga was stunned to listen to him say that the museum had a number of Zambian artefacts.

“It actually blew my thoughts, so I requested: ‘How come a rustic that didn’t have a colonial previous in Zambia had so many artefacts from Zambia in its assortment?'”

Within the nineteenth and early twentieth Centuries Swedish explorers, ethnographers and botanists would pay to journey on British ships to Cape City after which make their manner inland by rail and foot.

There are near 650 Zambian cultural objects within the museum, collected over the course of a century – in addition to about 300 historic pictures.

Girls’s Historical past Museum Zambia

Girls’s Historical past Museum ZambiaWhen Yonga and her digital museum co-founder Mulenga Kapwepwe explored the archives, they had been astonished to search out the Swedish collectors had travelled far and huge – a few of the artefacts come from areas of Zambia which might be nonetheless distant and arduous to achieve.

The gathering contains reed fishing baskets, ceremonial masks, pots, a waist belt of cowry shells – and 20 leather-based cloaks in pristine situation collected throughout a 1911-1912 expedition.

They’re constructed from the pores and skin of a lechwe antelope by the Batwa males and worn by the ladies or utilized by the ladies to guard their infants from the weather.

On the fur exterior are “geometric patterns, meticulously, delicately and fantastically designed”, Yonga says.

There are photos of the ladies sporting the cloaks, and a 300-page pocket book written by the one who introduced the cloaks to Sweden – ethnographer Eric Van Rosen.

He additionally drew illustrations displaying how the cloaks had been designed and took pictures of girls sporting the cloaks in several methods.

“He took nice pains to point out the cloak being designed, all of the angles and the instruments that had been used, and [the] geography and site of the area the place it got here from.”

The Swedish museum had not executed any analysis on the cloaks – and the Nationwide Museums Board of Zambia was not even conscious they existed.

So Yonga and Kapwepwe went to search out out extra from the group within the Bengweulu area in north-east of the nation the place the cloaks got here from.

“There is not any reminiscence of it,” says Yonga. “Everyone who held that data of making that exact textile – that leather-based cloak – or understood that historical past was not there.

“So it solely existed on this frozen time, on this Swedish museum.”

Girls’s Historical past Museum Zambia

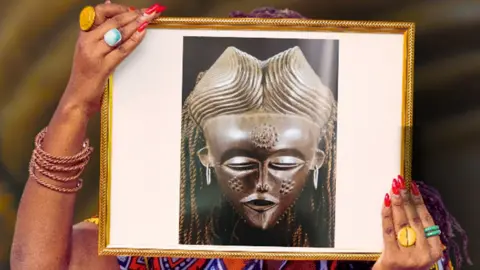

Girls’s Historical past Museum ZambiaOne in every of Yonga’s private favourites within the Body mission is Sona or Tusona, an historic, subtle and now not often used writing system.

It comes from the Chokwe, Luchazi and Luvale individuals, who reside within the borderlands of Angola, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Yonga’s personal north-western area of Zambia.

Geometric patterns had been made within the sand, on fabric and on individuals’s our bodies. Or carved into furnishings, wood masks used within the Makishi ancestral masquerade – and a wood field used to retailer instruments when individuals had been out looking.

The patterns and symbols carry mathematical ideas, references to the cosmos, messages about nature and the surroundings – in addition to directions on group life.

The unique custodians and lecturers of Sona had been girls – and there are nonetheless group elders alive who keep in mind the way it works.

They’re an enormous supply of information for Yonga’s ongoing corroboration of analysis executed on Sona by students like Marcus Matthe and Paulus Gerdes.

“Sona’s been probably the most well-liked social media posts – with individuals expressing shock and big pleasure, exclaiming: ‘Like, what, what? How is that this attainable?'”

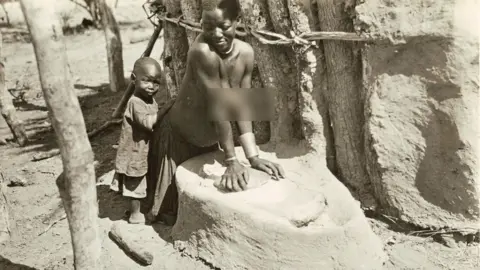

The Queens in Code: Symbols of Girls’s Energy put up features a {photograph} of a girl from the Tonga group in southern Zambia.

She has her palms on a mealie grinder, a stone used to grind grain.

Nationwide Museums of World Cultures

Nationwide Museums of World CulturesResearchers from the Girls’s Historical past Museum of Zambia found throughout a subject journey that the grinding stone was greater than only a kitchen software.

It belonged solely to the lady who used it – it was not handed right down to her daughters. As a substitute, it was positioned on her grave as a tombstone out of respect for the contribution the lady had made to the group’s meals safety.

“What would possibly appear like only a grinding stone is actually an emblem of girls’s energy,” Yonga says.

The Girls’s Historical past Museum of Zambia was arrange in 2016 to doc and archive girls’s histories and indigenous data.

It’s conducting analysis in communities and creating an internet archive of things which have been taken out of Zambia.

“We’re making an attempt to place collectively a jigsaw with out even having all of the items but – we’re on a treasure hunt.”

A treasure hunt that has modified Yonga’s life – in a manner that she hopes the Body social media mission can even do for different individuals.

“Having a way of my group and understanding the context of who I’m traditionally, politically, socially, emotionally – that has modified the way in which I work together on this planet.”

Penny Dale is a contract journalist, podcast and documentary-maker based mostly in London

Extra BBC tales on Zambia:

Getty Photographs/BBC

Getty Photographs/BBC

&w=1200&resize=1200,0&ssl=1)