Science retracts NASA arsenic micro organism paper after years of controversy

In 2010, within the waters of Mono Lake in California, NASA-funded scientists claimed to have discovered a microbe known as GFAJ-1 they stated rewrote biology. It had allegedly changed the phosphorus in its DNA with the poisonous aspect arsenic. The announcement, made at a high-profile press convention on December 2 that 12 months, shocked the world.

The findings, quickly printed within the journal Science, hinted that life might depend on a radically totally different chemistry. Lead creator and microbial geobiologist Felisa Wolfe-Simon declared, “Life as we all know it might be due for a revision.”

Hypothesis surged: had NASA stumbled onto alien biology?

Set the ball rolling

On July 24 this 12 months, Science introduced that it might be retracting the GFAJ-1 paper, practically 15 years after its splashy debut, citing shifting editorial requirements and lingering public confusion.

“It’s necessary to have any groundbreaking work independently evaluated earlier than drawing far-reaching conclusions,” College of Minnesota artificial biologist Kate Adamala stated. “We would like the general public to be excited, however the message should match the energy of the info.”

Mainstream media amplified the drama. One headline learn: ‘NASA Discovers Life Not As We Know It’.

Ivan Oransky, co-founder of Retraction Watch, a web site that tracks withdrawn papers and promotes analysis transparency, and government director of The Centre for Scientific Integrity, noticed the media blitz as pivotal. “With out the hype, this paper may by no means have been retracted.”

He pointed to NASA’s fashion of communication as a key issue within the storm that adopted in 2010.

“Traditionally, NASA hasn’t at all times had a respectful relationship with journalists,” he stated. “They’re nice at selling themselves, and generally at overselling.”

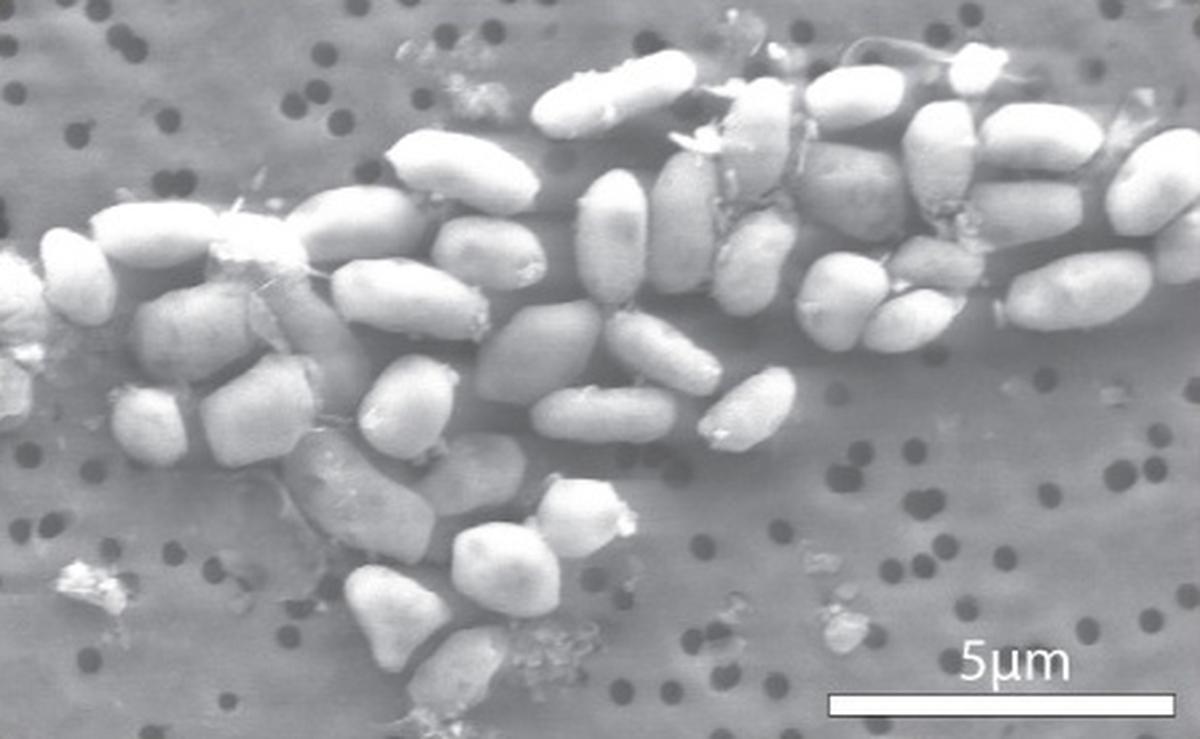

A microscopic view of GFAJ-1 micro organism.

| Picture Credit score:

NASA

Peer evaluation in public

To the folks at giant, the prospect of arsenic life hinted at alien biochemistry. However for a lot of scientists, the GFAJ-1 paper raised extra questions than solutions. Critics started stating that arsenate is unstable in water, so its function in DNA appeared chemically implausible.

“If true, this could have overturned practically a century of knowledge, however nothing within the chemistry recommended it was potential,” Steven Benner, an early critic and chemistry professor at College of Florida stated.

Others had been initially intrigued. “I used to be very excited and impressed. It was an enormous deal within the origins group,” Adamala, then a graduate scholar, stated.

However like many, her enthusiasm waned as flaws emerged. Microbiologist Rosemary Redfield turned a number one critic and one of many first replicators to disprove the findings.

“It’s a positive instance of how straightforward it’s for scientists to be misled by a lovely speculation and of why we’d like each formal peer evaluation and casual exterior scrutiny.”

By late December, the backlash gained traction. Blogs and Twitter (now X.com) turned the paper right into a case research on post-publication peer evaluation.

Sheila Jasanoff, professor of science and expertise research at Harvard, famous that whereas such public areas can foster useful crowd-sourced peer evaluation, additionally they threat overreach.

“As of late science, like true crime, has spilled exterior the constraints of formally authorised evaluation. Nevertheless, like all types of democratisation, such casual policing can run uncontrolled whether it is pushed by a mob mentality that’s out to disgrace or undermine a researcher or a analysis program.”

The unique staff stood by their findings — however by now the tone had shifted.

Proof falls aside

Over the subsequent 18 months, a number of labs examined the paper’s core assertion.

In 2012, Science printed two research that refuted it. Redfield’s staff discovered no arsenate in GFAJ-1’s DNA. Tobias Erb’s group confirmed the microbe nonetheless wanted phosphorus to develop, i.e. it hadn’t rewritten biology, simply tolerated low-phosphate circumstances.

Wolfe-Simon maintained that her staff’s strategies confirmed arsenic was integrated into DNA and had been strong sufficient to rebut Benner’s contamination claims.

Science didn’t retract or flag the paper, saying claims needs to be resolved by additional analysis, not editorial motion. And since no fraud was alleged, the rebuttals sufficed.

“The entire debate finally ends up circling across the semantics of phrases like ‘error’, ‘fraud’, ‘misconduct,’” Oransky stated. “However this paper, let’s be trustworthy, has been understood as unreliable since no less than 2012, if not earlier.”

Why science took so lengthy

For Benner, the GFAJ-1 paper mirrored variations in scientific views. Biologists noticed phosphorus as important, chemists knew arsenate’s instability, geologists accepted mineral substitutions, and astrobiologists embraced radical potentialities.

“It wasn’t that reviewers had been incompetent,” Benner stated. “They simply didn’t all communicate the identical scientific language.”

He noticed one other deeper flaw. NASA’s astrobiology group usually depends on consensus panels that falter when nobody challenges concepts exterior their area.

“Multidisciplinary science is crucial,” he stated, “however when it’s superficial, weak claims slip by way of. This wasn’t peer evaluation breaking down: it was totally different communities assuming they shared requirements whereas working from very totally different assumptions.”

Adamala echoed this concern: “Younger scientists in interdisciplinary fields ought to embrace steady peer evaluation, as reliance on collaborators’ experience can miss flaws that later scrutiny may catch.”

Correction sans closure

“They’re proper to retract a paper whose high-profile conclusions had been completely flawed,” Redfield stated.

One senior researcher famous that the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) pointers, which many journals have adopted as a measure to enhance analysis integrity, justify a retraction if the findings are unreliable. Right here, a number of labs discovered phosphate within the arsenate medium, undermining the paper’s core declare that the microbe grew by substituting arsenic for phosphorus.

“The expansion experiments on the coronary heart of the paper had been flawed,” the researchers stated. “Even when it was an trustworthy mistake, the core conclusions didn’t maintain up.”

Adamala stated that it’s a superb instance of self-regulation in science. “Slowly however absolutely, errors do get corrected.”

Oransky was extra measured: “Science is now performing on an expanded definition of retraction that’s in line with what’s been potential for a very long time, however hardly ever used.”

Not everybody sees it as black and white. Jasanoff warned that retractions can erase the very messiness that makes science work.

“Slightly than draw exhausting traces between fact and error, science advances by way of open debate,” she stated. “It’s higher to protect a file that reveals how scientists take a look at, problem, and refine their concepts, even when believable claims later show flawed.”

Benner, for his half, expressed fear that broadening retraction insurance policies might weaken the casual scrutiny that uncovered the paper’s flaws, elevating questions on balancing error correction with preserving the scientific course of.

Right now, the entire saga has reworked right into a cautionary story. Adamala stated the controversy could have forged a shadow over unique chemistry analysis in astrobiology, making scientists extra cautious about daring claims.

Who pays the worth?

Felisa Wolfe-Simon processes mud from Mono Lake to inoculate media to develop microbes on arsenic.

| Picture Credit score:

File photograph

Wolfe-Simon’s rise and fall was swift. In 2010, she was hailed for a possible revolution in biology. Two years later, she quietly exited each NASA and mainstream science, her analysis profession derailed by controversy and lack of funding.

“Good scientists would have responded by getting again into the lab and doing the required follow-up work. However these authors nonetheless don’t admit errors,” Redfield stated, pointing to their rebuttal letter in response to the retraction.

Ariel Anbar, a coauthor of the now retracted paper, stated, “Science cited no misconduct or particular mistake. We stand firmly by the integrity of our knowledge.”

He additionally criticised the journal for not sharing a weblog publish it printed relating to the retraction with the authors, calling it a breach of COPE pointers.

Oransky disagreed: “What guideline is that this referring to? Moreover, standing by your knowledge doesn’t imply there aren’t errors in it.”

Anbar additionally stated the staff rejected “the alleged error” and that it was raised in 2011 and rebutted in a peer-reviewed change.

“They could reject it,” Oransky replied, “however that appears to be the rationale for the retraction.”

Nonetheless, Oransky additionally stated Science’s retraction discover might have been clearer. He defined that retractions usually indicate misconduct, so when Science known as the paper unreliable however not unethical, it nonetheless put the authors on the defensive.

“You possibly can see that right here, they’re saying: ‘However there was no misconduct. No clear error.’”

Jasanoff stated she doesn’t see it fully as a person failure. She argued that the unusually lengthy delay till retraction could replicate much less a priority with scientific uncertainty and extra with a broader institutional tendency to handle status, particularly in an period of heightened fears over misinformation.

Wolfe-Simon’s arc underscored a stark fact: high-risk discoveries carry each acclaim and vulnerability. When science goes public, its failures play out simply as visibly as its triumphs, leaving lasting questions on the best way to right course with out crushing the folks behind the work.

A gradual machine

Peer-reviewers cleared GFAJ-1 and media hype propelled it, however shifting editorial norms greater than new knowledge undid it 15 years later. Oransky singled out Science’s editor-in-chief, Holden Thorp, for main that shift.

“Different journals have executed it, however he’s been persistently engaged in a means that encourages open dialog, regardless of whether or not folks agree with particular selections or not.”

That type of editorial openness, he added, could also be the actual legacy of the arsenic life saga.

Jasanoff, nonetheless, cautioned that each retraction dangers erasing the seen, iterative debate that builds belief. “It’s higher for folks to know that science strikes by way of trial and error, and gradual self-correction. It isn’t a binary. All science is provisional.”

Benner drew a parallel to the 1976 Viking missions, the place a untimely “no organics, no life” verdict in Science stifled debate. “Calling the ballgame early had an unlucky end result. It prevented the dialectic the scientific course of wants.”

The arsenic life case endures not due to its flawed declare, however for what it revealed in regards to the pressures shaping fashionable science: how spectacular findings — particularly from establishments like NASA — can short-circuit scrutiny, and the way correcting course means confronting the very techniques that made such claims irresistible within the first place.

Anirban Mukhopadhyay is a geneticist by coaching and science communicator from Delhi.