The rise of inexperienced tech is feeding one other environmental disaster

BBC

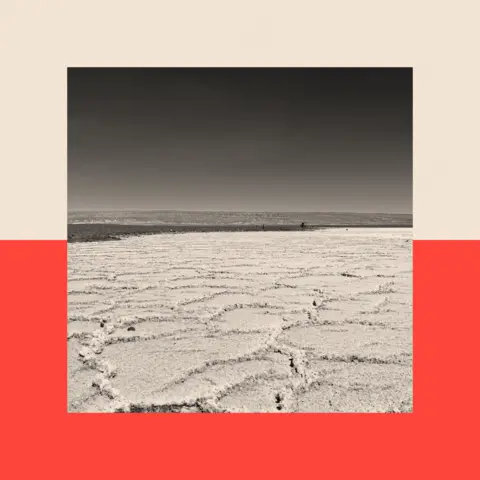

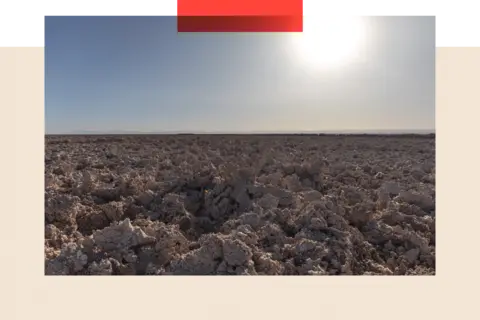

BBCRaquel Celina Rodriguez watches her step as she walks throughout the Vega de Tilopozo in Chile’s Atacama salt flats.

It is a wetland, recognized for its groundwater springs, however the plain is now dry and cracked with holes she explains had been as soon as swimming pools.

“Earlier than, the Vega was all inexperienced,” she says. “You could not see the animals by way of the grass. Now the whole lot is dry.” She gestures to some grazing llamas.

For generations, her household raised sheep right here. Because the local weather modified, and rain stopped falling, much less grass made that a lot tougher.

But it surely worsened when “they” began taking the water, she explains.

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBC“They” are lithium corporations. Beneath the salt flats of the Atacama Desert lie the world’s largest reserves of lithium, a mushy, silvery-white steel that’s a vital part of the batteries that energy electrical vehicles, laptops and photo voltaic vitality storage.

Because the world transitions to extra renewable vitality sources, the demand for it has soared.

In 2021, about 95,000 tonnes of lithium was consumed globally – by 2024 it had greater than doubled to 205,000 tonnes, based on the Worldwide Power Company (IEA).

By 2040 it is predicted to rise to greater than 900,000 tonnes.

A lot of the enhance might be pushed by demand for electrical automobile batteries, the IEA says.

Locals say environmental prices to them have risen too.

So, this hovering demand has raised the query: is the world’s race to decarbonise unintentionally stoking one other environmental downside?

Flora, flamingos and shrinking lagoons

Chile is the second-largest producer of lithium globally after Australia. In 2023, the federal government launched a Nationwide Lithium Technique to ramp up manufacturing by way of partly nationalising the trade and inspiring personal funding.

Its finance minister beforehand mentioned the rise in manufacturing might be by as much as 70% by 2030, though the mining ministry says no goal has been set.

This yr, a significant milestone to that’s set to be reached.

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCA deliberate joint enterprise between SQM and Chile’s state mining firm Codelco has simply secured regulatory approval for a quota to extract not less than 2.5 million metric tonnes of lithium steel equal per yr and increase manufacturing till 2060.

Chile’s authorities has framed the plans as a part of the worldwide battle towards local weather change and a supply of state earnings.

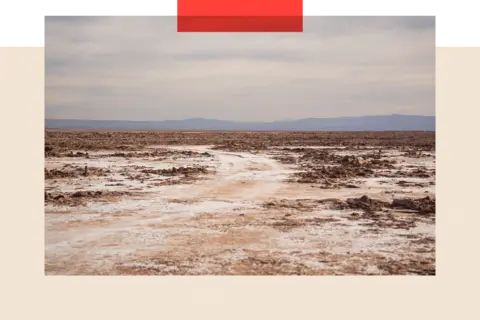

Mining corporations predominantly extract lithium by pumping brine from beneath Chile’s salt flats to evaporation swimming pools on the floor.

The method extracts huge quantities of water on this already drought-prone area.

Ben Derico/BBC

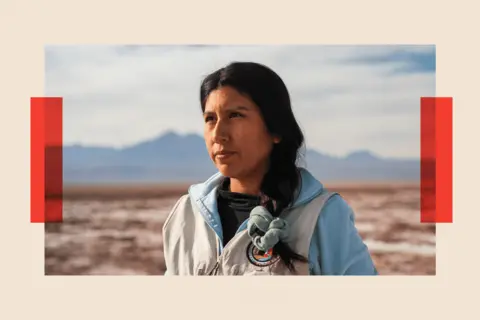

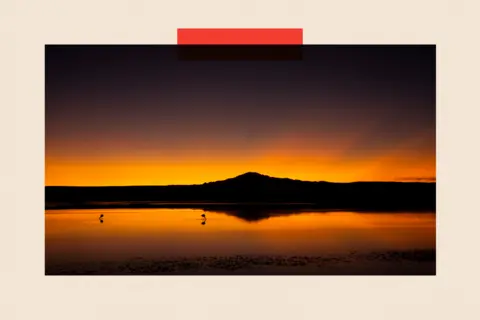

Ben Derico/BBCFaviola Gonzalez is a biologist from the native indigenous neighborhood working within the Los Flamencos Nationwide Reserve, in the midst of the Atacama Desert, house to huge salt flats, marshes and lagoons and a few 185 species of birds. She has monitored how the native atmosphere is altering.

“The lagoons listed here are smaller now,” she says. “We have seen a lower within the copy of flamingos.”

She mentioned lithium mining impacts microorganisms that birds feed on in these waters, so the entire meals chain is affected.

She factors to a spot the place, for the primary time in 14 years, flamingo chicks hatched this yr. She attributes the “small reproductive success” to a slight discount in water extraction in 2021, however says, “It is small.”

“Earlier than there have been many. Now, just a few.”

The underground water from the Andes, wealthy in minerals, is “very previous” and replenishes slowly.

“If we’re extracting lots of water and little is coming into, there’s little to recharge the Salar de Atacama,” she explains.

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Company through Getty Photographs

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Company through Getty PhotographsInjury to flora has additionally been present in some areas. On property within the salt flats, mined by the Chilean firm SQM, virtually one-third of the native “algarrobo” (or carob) bushes had began dying as early as 2013 as a result of impacts of mining, based on a report revealed in 2022 by the US-based Nationwide Assets Protection Council.

However the challenge extends past Chile too. In a report for the US-based Nationwide Assets Protection Council in 2022, James J. A. Blair, an assistant professor at California State Polytechnic College, wrote that lithium mining is “contributing to situations of ecological exhaustion”, and “might lower freshwater availability for natural world in addition to people”.

He did, nonetheless, say that it’s tough to seek out “definitive” proof on this matter.

Mitigating the injury

Environmental injury is after all inevitable in relation to mining. “It is onerous to think about any sort of mining that doesn’t have a adverse impression,” says Karen Smith Stegen, a political science professor in Germany, who research the impacts of lithium mining internationally.

The difficulty is that mining corporations can take steps to mitigate that injury. “What [mining companies] ought to have achieved from the very starting was to contain these communities,” she says.

For instance, earlier than pumping lithium from underground, corporations may perform “social impression assessments” – opinions which keep in mind the broad impression their work could have on water, wildlife, and communities.

Getty Photographs

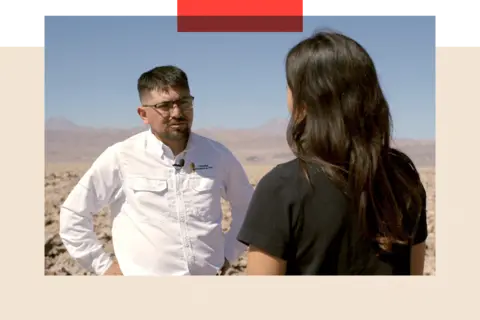

Getty PhotographsFor his or her half, mining corporations now say they’re listening. The Chilean agency SQM is without doubt one of the foremost gamers.

At one among their crops in Antofagasta, Valentín Barrera, Deputy Supervisor of Sustainability at SQM Lithium, says the agency is working intently with communities to “perceive their considerations” and finishing up environmental impression assessments.

He feels strongly that in Chile and globally “we want extra lithium for the vitality transition.”

He provides that the agency is piloting new applied sciences. If profitable, the concept is to roll these out of their Salar de Atacama crops.

These embrace each extracting lithium straight from brine, with out evaporation swimming pools, and applied sciences to seize evaporated water and re-inject it into the land.

“We’re doing a number of pilots to know which one works higher as a way to enhance manufacturing however cut back not less than 50% of the present brine extraction,” he mentioned.

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCHe says the pilot in Antofagasta has recovered “multiple million cubic metres” of water. “Beginning in 2031, we’re going to begin this transition.”

However the locals I spoke to are sceptical. “We consider the Salar de Atacama is like an experiment,” Faviola argues.

She says it is unknown how the salt flats may “resist” this new expertise and the reinjection of water and fears they’re getting used as a “pure laboratory.”

Sara Plaza, whose household additionally raised animals in the identical neighborhood as Raquel, is anxious concerning the modifications she has seen in her lifetime.

She remembers water ranges dropping from as early as 2005 however says “the mining corporations by no means stopped extracting.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCSara turns into tearful when she speaks concerning the future.

“The salt flats produce lithium, however in the future it should finish. Mining will finish. And what are the individuals right here going to do? With out water, with out agriculture. What are they going to reside on?”

“Perhaps I will not see it due to my age, however our youngsters, our grandchildren will.”

She believes mining corporations have extracted an excessive amount of water from an ecosystem already struggling from local weather change.

“It is very painful,” she provides. “The businesses give the neighborhood somewhat cash, however I might favor no cash.

“I might favor to reside off nature and have water to reside.”

The impression of water shortages

Sergio Cubillos is head of the affiliation for the Peine neighborhood, the place Sara and Raquel reside.

He says Peine has been compelled to vary “our complete consuming water system, electrical system, water therapy system” due to water shortages.

“There’s the difficulty of local weather change, that it would not rain anymore, however the primary impression has been brought on by extractive mining,” he says.

He says because it began within the Nineteen Eighties, corporations have extracted tens of millions of cubic metres of water and brine – lots of of litres per second.

“Choices are made in Santiago, within the capital, very removed from right here,” he provides.

He believes that if the President desires to battle local weather change, like he mentioned when he ran for workplace, he must contain “the indigenous individuals who have existed for millennia in these landscapes.”

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu through Getty Photographs

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu through Getty PhotographsSergio understands that lithium is essential for transitioning to renewable vitality however says his neighborhood shouldn’t be the “bargaining chip” in these developments.

His neighborhood has secured some financial advantages and oversight with corporations however is anxious about plans to ramp up manufacturing.

He says whereas in search of applied sciences to cut back the impression on water is welcome that “cannot be achieved sitting at a desk in Santiago, however quite right here within the territory.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCChile’s authorities stresses there was “ongoing dialogue with indigenous communities” they usually have been consulted over the brand new Codelco-SQM three way partnership’s contracts to deal with considerations round water points, new applied sciences and contributions to the communities.

It says growing manufacturing capability might be primarily based on incorporating new applied sciences to minimise the environmental and social impression and that the excessive “worth” of lithium on account of its position within the world vitality transition may present “alternatives” for the nation’s financial growth.

Sergio although worries about their space being a “pilot challenge” and says if the impression of recent expertise is adverse, “We’ll put all our energy into stopping the exercise that might finish with Peine being forgotten.”

A small a part of a world dilemma

The Salar de Atacama is a case examine for a world dilemma. Local weather change is inflicting droughts and climate modifications. However one of many world’s present options is – based on locals – exacerbating this.

There’s a widespread argument from individuals who assist lithium mining: that even when it damages the atmosphere, it brings enormous advantages through jobs and money.

Daniel Jimenez, from lithium consultancy iLiMarkets, in Santiago, takes this argument a step additional.

He claims that environmental injury has been exaggerated by communities who desire a pay-out.

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Company through Getty Photographs

Lucas Aguayo Araos/Anadolu Company through Getty Photographs“That is about cash,” he argues. “Firms have poured some huge cash into enhancing roads, faculties – however the claims of communities actually return to the very fact they need cash.”

However Prof Stegen is unconvinced. “Mining corporations at all times wish to say, ‘There are extra jobs, you are going to get more cash’,” she says.

“Nicely, that is not significantly what lots of indigenous communities need. It really could be disruptive if it modifications the construction of their very own conventional financial system [and] it impacts their housing prices.

“The roles should not the be all and finish all for what these communities need.”

Ben Derico/BBC

Ben Derico/BBCIn Chile, these I spoke to did not discuss wanting more cash. Nor are they against measures to deal with local weather change. Their foremost query is why they’re paying the value.

“I feel for the cities perhaps lithium is nice,” Raquel says. “But it surely additionally harms us. We do not reside the life we used to reside right here.”

Faviola doesn’t assume electrifying alone is the answer to local weather change.

“All of us should cut back our emissions,” she says. “In developed nations just like the US and Europe the vitality expenditure of individuals is way larger than right here in South America, amongst us indigenous individuals.”

“Who’re the electrical vehicles going to be for? Europeans, Individuals, not us. Our carbon footprint is way smaller.”

“But it surely’s our water that is being taken. Our sacred birds which might be disappearing.”

High picture credit score: Getty Photographs. Further reporting: George Wright

BBC InDepth is the house on the web site and app for the most effective evaluation, with contemporary views that problem assumptions and deep reporting on the largest problems with the day. And we showcase thought-provoking content material from throughout BBC Sounds and iPlayer too. You’ll be able to ship us your suggestions on the InDepth part by clicking on the button beneath.